Creationists believe that all living things were designed in roughly their current form by God, who is omnipotent and omniscient. To bolster this point they like to point out how some natural structures display clockwork like workings. Many parts appear to work in unison. If evolution were the cause then how did each of those little parts (which would be useless by itself) come to be as the result of only luck?

One example that is often used if the eye. Sometimes this argument is coupled with a Darwin quote, where in Origin of Species Darwin muses “To suppose that the eye … could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest degree.” omitting the important following sentence “Reason tells me, that if numerous gradations from a simple and imperfect eye to one complex and perfect can be shown to exist, each grade being useful to its possessor, as is certain the case; if further, the eye ever varies and the variations be inherited, as is likewise certainly the case; and if such variations should be useful to any animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection, should not be considered as subversive of the theory.”

So there are arguments on both sides. And as-it-so-happens, these arguments look like scientific hypotheses. That’s interesting, maybe we can test them?

Hypothesis one can be formulated as follows: “God designed the eyes of all creatures, including human beings.” What predictions can we make from that?

Well, the eye should look like something God designed. God is omnipotent and omniscient, so he’s the best designer possible. He knows everything and can do anything. The eye should be as close to flawless as anything which is not God can be. And while things in the world are always imperfect, the design that God makes for them is not a thing in the world. In other word, eyes should be imperfect but their design should not be.

Hypothesis two can be formulated as follows: “The eye came about through the process of evolution, or natural selection through heritable traits.” What predictions can we make from that?

Well there are lots of creatures with eyes. Those creatures must have a common ancestor which also had eyes, or several ancestors if eyes developed simultaneously in different populations (that is, it matters if eyes are the result of convergent or divergent evolution).

Further, eyes should look like the kind of things that came to be as a result of a process of gradual heritable changes. They should not look like they appeared out of nowhere perfectly formed.

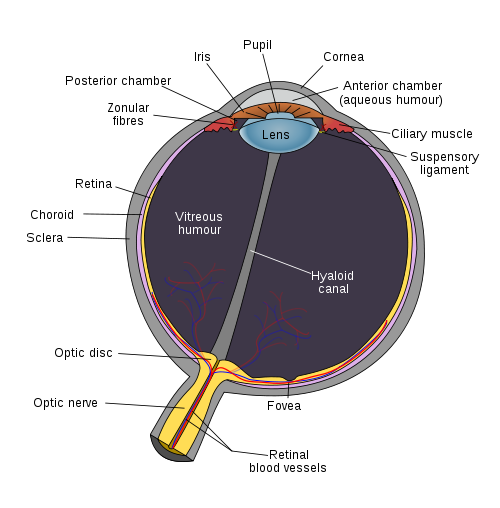

Human eyes are well understood, so we’ll look at a human eye to test these hypotheses. Eyes are sense organs that act as photo-detectors. They gather information through special cells called photo-receptors and transmit that information to the brain. The actual photo-receptors are cells called rods and cones which line the back of the eye, and which undergo chemical changes when light interacts with special light-detecting chemicals in them. The other parts of the eye function to support these cells by protecting them, transmitting the information they collect, or assisting them in detecting light, for instance by focusing light entering the eye on the retina.

The eye looks complicated with plenty of small, interrelated parts which wouldn’t work or be helpful on their own. But let’s look deeper.

Now suppose we’re evolutionary biologists. We want to imagine the likely evolutionary history of the eye so we can make a hypothesis about how eyes formed. What would the absolute simplest eye be, the original eye which could form by itself and still be useful?

Probably a lone photoreceptor cell, right? What use is an optic nerve with nothing at the end, or a cornea that focuses light onto nothing. But a cell that can detect light and tell the brain, that’s handy albeit crude.

But these cells are using all their ATP just to detect light. They can’t transmit information quickly, and speed counts big time in the evolutionary world. So you would expect some kind of support cells to develop to speed this up. And of course these cells are sensitive and important, so protection should also develop. These things would come about after though.

Now you would expect the same parts to form already perfect if God made it. But would the two eyes look the same?

This is a diagram of cells in the back of the human eye. It looks kind of complicated, but here’s what you need to know. The far right is the back of the eye, and moving to the left moves you toward the front of the eye. The long cells at the back of the eye are the photo-receptor cells, the cells which actually respond to light. The cells in from of them are support cells called Ganglia, which take information from the photo-receptors, condense it, and send it quickly to the brain.

Now something should occur to you instantly. Why are the photo-receptors behind the support cells? Don’t those cells get in the way of the light? They do, and in fact it’s worse than that. Those support cells need to get information to the brain, which is on the other side of the photo-receptors. They all meet and cross the photo-receptors at a point, and at that point there are no photo-receptors. There is, in other words, a blind spot built in your vision. Find yours here.

Now I’m not as smart as God, but that doesn’t seem like good design. Why would your eye be built with a blind spot? As it turns out, cephalopods like octopi have eyes with a different evolutionary history than vertebrates. They have a unique kind of photoreceptor that is coded for by a different gene than the one that codes the rods and cones of vertebrates (the fact that the same gene codes all vertebrate eyes is strong evidence for evolution by the way, as it suggests a common history for all vertebrate eyes). Cephalopod eyes have other difference too. Most notably, their optic nerve is behind their photo-receptors. In other words, the humble squid has better eyes than you, at least in-so-far-as it doesn’t have a blind spot.

Now if human beings are God’s crowning achievement, designed carefully in his own image, then why did he do a worse job designing our eyes than he did designing squid eyes? It should be obvious to anyone that the human eye could be better, it could have the ganglia behind the photo-receptors like in an octopus’ eye. That would eliminate the blind spot and let more light hit the receptors, letting the eye work more efficiently. I can’t see how that wouldn’t be an improvement, and God would not have designed something with a fundamental flaw unavoidably inherent. This is not the same as designing human hearts that will ultimately fail, this is a design which by an avoidable feature makes the product of that design worse at the task it is designed for, and does so necessarily and in all instances. That is, not only are our eyes imperfect but they are designed in a way that makes them worse than they could be.

On the other hand, if the eye developed step by step starting from a lone photoreceptor cell then a stacked retina makes sense – once the photo-receptors grow at the back of the eye where else could ganglia go if not in front of them? Vertebrate eyes are located in hard bony skulls after all. And evolution doesn’t care if a solution is pretty or perfect; the results are all that matter. If ganglia that interfere with light are still a net benefit to the organism then natural selection couldn’t care less.

So we’ve made two hypotheses with two different predictions. Hypothesis one said that if God made eyes, they should look like something God made. Hypothesis two said that is eyes evolved, they should look like something that evolved. We gathered data by looking at the retina of human and cephalopod eyes. And we saw that eyes are designed with a blind spot in them, which is the kind of thing evolved structures might have but God designed structures would not have. So as good scientists we are obliged to discard this version of hypothesis one and treat hypothesis two, the evolutionary origin of the eye, as corroborated.